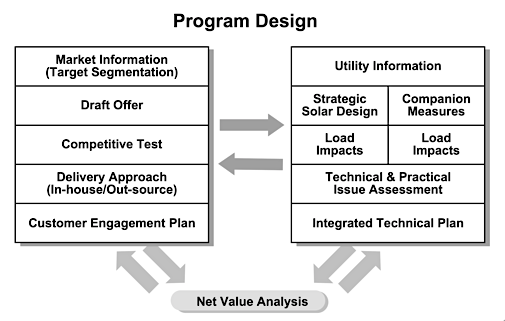

You can see the challenge in the diagram below, of a best-practice program-design process. Customer-driven planning steps interact with utility-driven steps, leading to a draft program plan—and then a preliminary economic analysis leads back to another cross-departmental go-round. It’s a bit messy, but for the most part, it’s unavoidable. Some utilities may tell one program manager to “just do it,” without much involvement from other departments, but usually that strategy leads to implementation delays, higher program costs, under-performance, and awkward meetings after all, with those work groups that simply need to be at the table.

1) Consider your counterparts in different departments as stakeholders. Just as the solar program manager has a stake in the outcome of a new community solar program, so do the folks in engineering, customer service, and IT. Find out what matters to each of the people you’ll have to work with, including what other pressures they’re under and how they see ongoing changes within the utility as a whole. Just as there are widely differing stakeholder views in the community, there are widely differing view within any utility. Ask, listen, and expect some compromise.

2) Apply marketing savvy inside the utility, as well as outside it. I used to teach a unit for the Association of Energy Services Professionals on Internal Marketing. Why not do a little research to consider not only your colleagues’ professional motivations, but also to answer such questions as, Do they have different decision-making styles? Do they prefer different ways of receiving and presenting information? Are there commonalities that bring people in different departments together?

3) Make it about the customer. Internal stakeholders will have their differences, but a unified focus on the customer can ease a lot of tension. The CSVP process diagram puts utility technical and economic concerns up front, too, but even those concerns, such as resource costs, grid management, billing processes, and so on are ultimately driven by the mission to serve customers better.

4) Reward the broader view. The solar program manager or program designer is often more of a generalist than many of the other internal stakeholders. Sometimes this person has a technical background, or sometimes a background in marketing or finance. But there will always be folks with more degrees and experience in a particular specialty at the table. Accept and share the fact that when it comes to community solar broader is better. The common playing field should be a place where internal experts come to work together, speaking plainly and striving to make the whole, integrated program succeed.

5) Come together around an exciting campaign or event. Collaborate to develop a program design and implementation schedule that diverse internal stakeholder can work toward and celebrate together. The program designer and manager should keep everyone—even the folks deep in the trenches of IT or engineering—informed about planning progress (such as a good word from the CEO!) or progress on the roll-out. By planning around an event, such as a ribbon-cutting or reception for community solar subscribers, the planner can invite cross-departmental players and publicly recognize the whole team.

6) Consider working with an outside innovator. Community solar innovators may raise some solutions that disrupt the organizational status quo, but sometimes—and in the right measure—that’s a good thing.

Finally, a word about the limits of staff-led collaborations. The fact is, such efforts are no substitute for leadership, which comes from the top. Some utilities don’t even have an open network for sustained collaboration; they have silos that often act as closed systems, with their own cultures and success-measures that do not reward shared efforts. In such cases, top-management has to take the lead, or a cross-departmental program success will not only be difficult, but it will almost surely be even harder to achieve again. On this point, I like to cite one of our industry’s program-evaluation pioneers, Jane Peters. She once interviewed numerous utility program evaluators, to see what, if anything, most successful programs had in common. What did she find? The top predictor of program success is executive-level support.

If you don’t have that, how do your get it? We'll have to cover that question in another blog. For now, I hope you will share these thoughts across your organization—including sending it, for consideration, to the top.