By Jill Cliburn

Here's a quick take on our streamlined approach to community solar analytics, aimed at keeping community solar in the community. You know the challenge. So many utilities nationwide have been critiqued for high premium pricing on local community solar. Some offer a market-based, remote solar product as a solution. Our approach is aimed squarely at solving that problem and bringing the premium on local community solar down to a range of two cents or less. That's the range market researchers describe (consistently!) as the boundary for customer acceptance.

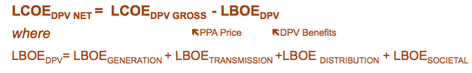

You might enjoy our more detailed discussion on this topic, presented on a recent CSVP webinar. We also have posted a deep dive into this topic in the Assessment section of our community solar Solutions toolbox. Here, I will focus on one key observation, often missed by utility analysts and rate designers, i.e., that true cost-based pricing for distributed solar is not simply a pass-through of the solar power purchase agreement (PPA) cost. Yes, the PPA is based on the levelized cost of energy (LCOE), but that LCOE is set from a solar-developer perspective. Put bluntly, it's gross. It is defined simply as the net present value (NPV) of project costs divided by the NPV of generation (kWh), evaluated over the life of the project. But from the utility perspective, distributed energy resources provide strategic benefits, too. The utility's net LCOE must include both the levelized costs of solar and also its incremental levelized benefits.

The generic equations for this net LCOE are:

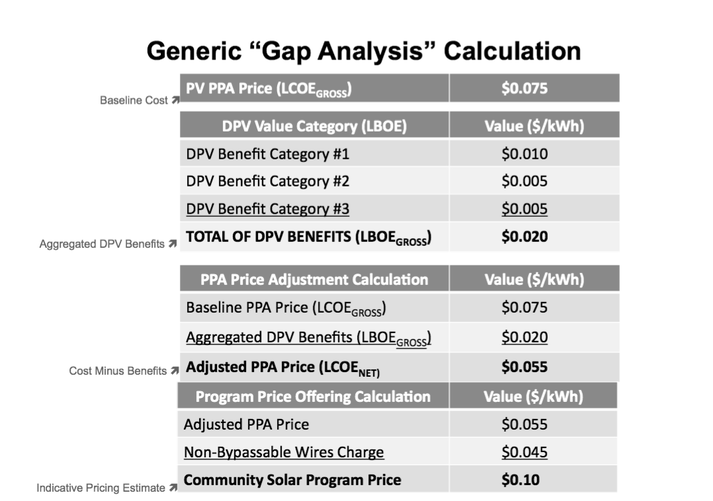

You can think of the true net LCOE as a benefits-adjusted PPA. It may be used to compare the utility's community solar resource options—e.g., a local project with grid benefits vs. a large, remote solar project, or a half-dozen similar local projects vs. a standard large-scale system. Further, the benefits-adjusted PPA can be applied readily as a pricing solution on the customer bill. CSVP's Sample Pricing Gap Analysis chart below summarizes how all this works. (Note that the values are for illustrative purposes only.)

Many utilities are permitted to "pass through" a benefits-adjusted PPA price instead of passing through the gross LCOE-based PPA price to community solar customers. The CSVP has verified this with at least two of its Utility Forum members; we're interested in talking with more. But we've all seen something like this happen in solar–and I would add some good stories from the wind industry, too–when a determined VP or CEO would tell the analysts to "sharpen their pencils" and make the economics work for a clearly desirable project.

Now, an important parenthetical: Yes, it is possible for some utilities to offer community-scale solar today without charging any premium at all. We've heard of a few cases where solar is the a least-cost resource, so a simple pass-through of the gross LCOE already beats the average retail cost of energy. That's no excuse to stop short, without considering clear benefits (for example, avoided transmission costs on distributed PV) and calculating the net LCOE. When net costs are low, opportunities emerge to target lower-income customers or to support value-added solar-plus project designs.

For many readers, this analytic approach looks familiar and hardly innovative--except in how it is applied. In contrast to a typical value-of-solar analysis, which attempts to identify and set all relevant benefits, this approach seeks a minimum list of benefits, associated with a specific program/acquisition. The goal is simply to reach a target net LCOE. Typically, the analyst would ask utility staff to provide ranges for each candidate value, and to apply caveats as needed. The analyst also may offer strategic improvements to the baseline project design, e.g., using a particular carport structure, single-axis tracker, or fleet deployment. If accepted, strategic design improvements can increase the levelized benefits of energy (LBOE) for the community solar project and make strong progress toward competitive pricing.

The CSVP has applied this process to three utility cases so far: 1) A northern California municipal utility comparing a DPV-inclusive portfolio with a single centralized PV buy; 2) A Southwestern utility where DPV--and even carport solar--benefits add up; and 3) a low-cost wholesale utility in the Mountain West, hoping to offer local community solar, while minimizing the premium on pricing. The differences from case to case are instructive, but in each case, a short list of benefits, conservatively estimated, has proven adequate to meet the target price. I think that's compelling, and I hope you'll dive into our posted materials for detail. One very practical scenario, using a mixed fleet of centralized and local, distributed solar projects is included here, or contact us with your questions.

In utility and peer reviews so far (the cases were completed this year), this process has scored high marks for its focus on building utility decision-makers' support; on speeding the path to more competitive program design and pricing, and on pushing the community solar market forward. It was noted that in a few markets, utilities just can't monetize some fairly obvious benefits, due to problems in market structure. But even then, it is likely that utilities can find alternative benefits to meet a reasonable pricing target. In time, sweeping policy advances may dramatically change utility understanding of the solar value proposition, but we can start with solutions, like this one, that work for today.

This blog is based on a poster presentation that will be featured at Solar Power International 2017, in Las Vegas, NV, this September. See you there!