by Jill Cliburn

When the CSVP touts community solar as an exciting way to roll out energy storage innovations, we often cite pilot-scale introductions, with customer-side thermal storage. Steele Waseca, a co-op in Minnesota, set the pace for that strategy in 2015, when it introduced a 100-kW community solar project, where each solar share comes with an option for a free, load-controlled electric water heater. That strategy reduced base-case program costs by 70% and allows the utility to use more wind energy, usually at night. We’ve seen similar thermal storage offers tied directly to community solar, and we believe the future for such programs is bright.

We’ve also seen battery storage projects (on the customer-side, at Green Mountain Power and on the utility side, at Austin Energy) that are ripe for pairing with community-solar. But through fall 2017, the business models for community solar plus batteries seemed a little ways off. And then came Fayetteville....

Soon after our Solar Plus Storage guide came out last fall, we participated in the American Public Power Association Customer Connections Conference. A presentation from the Fayetteville, North Carolina, Public Works Commission (PWC) captivated the audience with its strong business case for utility-led community solar plus battery storage.

That project is still in the works, with construction and market introduction expected this summer. We might have kept mum on its progress, but we’ve heard of at least one other public power project that is taking a serious look at the model, and there are others that should. It is a case, as we often see during an early-adoption phase, of a utility problem that triggers opportunity. If you’ve got this problem, consider…

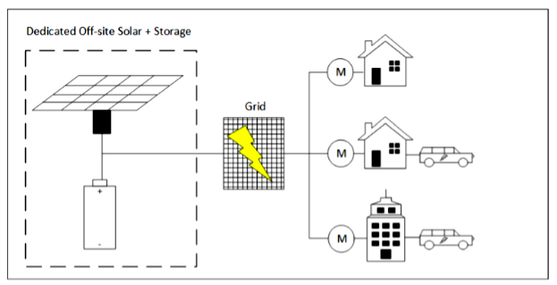

PWC has specified 1-MW PV array with single-axis tracking, along with a 500-kW/1,000 kWh lithium-ion (Li-on) battery. Fayetteville customers have been outspoken in favor of community solar, and as they learn about storage, they like it, too. By going with solar plus storage, PWC can avoid a hefty monthly coincident peak demand charge from its power suppler, Duke Energy Progress. The local utility can pass that savings along, to make the program a win-win for participants, the utility and the community overall.

According to a study published by the North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center, with the U.S. Department of Energy (SunShot) and PWC, the savings on demand charges that accrue from storing solar energy when it is abundant and discharging it during the coincident-demand period is the number one economic driver for this model. In addition, the solar design, using single access tracking, picks up greater on-peak solar generation, and the whole project picks up value, based on compliance with the state’s RPS.

Thanks to good, solar-plus design, this project will nail the coincident peak with almost perfect accuracy (“95% of months,” according to the NCCETC report). A few other benefits of the selected business model include utility ownership from the start, rather than use of a long-term PPA or flip structure. Other utilities may find third-party structures capable of meeting economic requirements, but as a municipal utility, PWC found that self-financing and long-term ownership could work for them.

Late in 2017, utility program designers began to worry about the impact of the impending solar tariff regime on the project, according to Nadav Enbar, an analyst for EPRI who reported on this project for an upcoming EPRI member report. It seems likely that, with the continuing decline of storage costs and the relatively manageable conclusion of the tariff debate, the project will still pencil out, as PWC moves from RFQ to RFP in its internal procurement process.

Wholesale demand charges are not as prevalent as they once were, but many utilities still pay them, and sometimes they are quite steep. In fact, this business model seems to take a lesson from the increasing interest among retail commercial customers, especially in states like California, to use solar plus storage for demand arbitrage. It may be that emerging rate structures at the retail and wholesale level will change the particulars of on-peak energy avoidance. Yet we are willing to bet that, with increasing solar generation and the development of an ever-steeper ramp in evening utility demand, emerging rate structures will continue—or even intensify—the incentives for PV system dispatch to the grid. Advanced battery systems and new control strategies for customer-side demand response can adapt to the most likely changes in rate structures. Utilities like PWC are deciding that now is the time to engage with customers on this increasingly important solution.